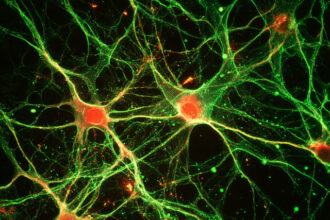

In a revolutionary study published in the journal Cell Reports, researchers have revealed that neurotransmitters are activated in the human brain during the emotional processing of language, providing new insights into how words are interpreted in terms of their significance. The research, spearheaded by an international team led by Virginia Tech scientists, advances our understanding of the impact of language on human decision-making and mental health. The study, orchestrated by computational neuroscientist Read Montague, a professor at the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute at VTC and director of the institute’s Center for Human Neuroscience Research, explores for the first time how neurotransmitters manage the emotional content of language, a capacity uniquely human.

This pioneering research, featured in the January 28 issue of Cell Reports, connects the biological with the symbolic, linking neural processes—presumably evolved for survival across diverse species throughout the ages—with the complexity of human communication and emotion. Montague, co-corresponding and co-senior author of the study, discusses the traditional view of brain chemicals like dopamine and serotonin as messengers that convey the emotional values of experiences. He suggests that these chemicals are released explicitly in targeted areas of the brain when the emotional meaning of words is processed, implying a broader role for brain systems that have evolved to help us react to our environment and now influence how we process language, a key factor in human survival.

The research marks the first time dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine release has been simultaneously measured in humans concerning the complex brain dynamics behind language interpretation and reaction. Montague notes that while the emotional significance of words interacts with multiple neurotransmitter systems, each system reacts differently, emphasizing that no single brain region or neurotransmitter solely manages this activity. The relationship between chemicals and emotions is intricate.

The neurochemical measurements were conducted on patients undergoing deep brain stimulation surgery for essential tremor treatment or for implantation of leads to monitor seizures in epilepsy patients, explicitly targeting the thalamus and the anterior cingulate cortex. While emotionally charged words were displayed on a screen, measurements were captured using sophisticated electrodes in these regions, revealing that the emotional tone of words influenced neurotransmitter release. Researchers identified distinct patterns linked to the emotional tone, anatomical areas, and which hemisphere of the brain was active.

An unexpected result emerged from the thalamus, a region not previously associated with language or emotional processing, where significant neurotransmitter changes occurred in response to emotional words. William “Matt” Howe, an assistant professor with the School of Neuroscience at Virginia Tech and co-senior author of the study, suggests that this finding indicates even brain regions not typically linked to emotional or linguistic processing might still access and use emotionally significant information, potentially influencing behaviours like movement.

Building on prior studies, this research underscores a uniquely human trait: the emotional content of written words. Unlike animals, humans can understand words, their context, and meanings, and this study examines how neurotransmitter systems process words with different emotional weights. This supports the theory that these systems, which evolved to ensure survival, now facilitate language interpretation. This foundational study not only offers profound insights into the biological underpinnings of language but also sets the stage for future research into how our brains process the emotional content of language.

More information: Seth Batten et al, Emotional words evoke region- and valence-specific patterns of concurrent neuromodulator release in human thalamus and cortex, Cell Reports. DOI: 10.1016/j.celrep.2024.115162

Journal information: Cell Reports Provided by Virginia Tech