A new study published in Aging (Aging-US), Volume 17, Issue 7, on 21 July 2025, is titled “Association of DNA methylation age acceleration with digital clock drawing test performance: the Framingham Heart Study.” The research team was led by first author Zexu Li of the Department of Anatomy and Neurobiology at Boston University’s Chobanian and Avedisian School of Medicine, with corresponding author Chunyu Liu, who also holds appointments at the Boston University School of Public Health. Their investigation sheds light on the relationship between biological ageing at the molecular level and long-term cognitive performance.

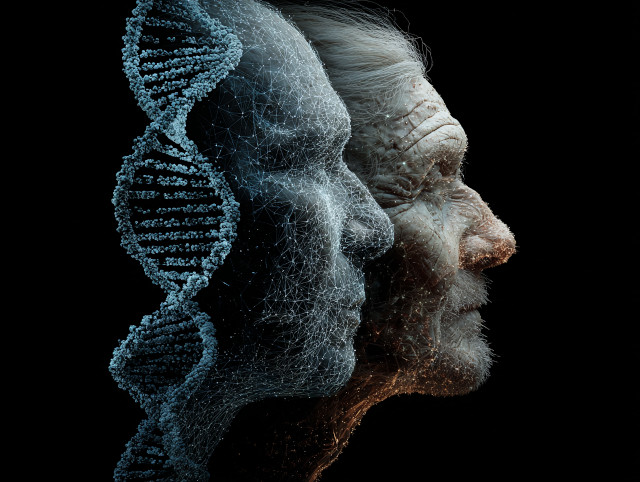

The researchers found that individuals who exhibited signs of faster biological ageing tended to perform less well on a digital cognitive test administered seven years later. This suggests that the rate at which DNA undergoes age-related molecular changes may influence how the brain functions as people grow older. The findings emphasise that biological, rather than simply chronological, age might provide a more accurate measure of an individual’s vulnerability to cognitive decline.

The analysis drew on data from 1,789 participants in the Framingham Heart Study, a long-running cohort that has provided extensive insights into health and ageing. To estimate biological age, the team examined DNA methylation (DNAm) patterns—chemical modifications to DNA known to accumulate over time and commonly referred to as “epigenetic ageing.” Cognitive function was measured using the digital Clock Drawing Test (dCDT), a computerised version of the traditional assessment tool. The dCDT evaluates memory, processing speed, motor control, and spatial reasoning, producing both overall and domain-specific scores.

Results showed that greater epigenetic age acceleration was significantly associated with lower cognitive scores, particularly among participants over 65 years of age. Among the different epigenetic ageing metrics, the DunedinPACE measure showed the strongest correlation with poorer cognitive function across age groups. Other indices, such as Horvath and PhenoAge, were linked to lower performance only in the older participants. Declines were most pronounced in areas related to motor ability and spatial reasoning, both essential for everyday functioning.

The study also investigated proteins included in the GrimAge epigenetic clock, a blood-based biomarker of ageing. Two proteins in particular—plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI1) and adrenomedullin (ADM)—were closely associated with poorer cognitive performance, again with the most potent effects seen in older individuals. These findings point to a broader connection between systemic ageing processes in the body and mental as well as motor decline in the brain, highlighting the intertwined nature of ageing across multiple biological systems.

Taken together, the results provide compelling evidence that accelerated biological ageing is linked to declines in memory, thinking speed, and motor control. The authors argue that epigenetic age is likely a better predictor of cognitive decline than chronological age. Because the dCDT is automated, precise, and easy to administer, it could become a valuable tool for early detection of brain ageing when combined with DNA methylation measures. Ultimately, this research opens new possibilities for identifying individuals at risk of cognitive impairment and developing more targeted approaches to support healthy ageing in older populations.

More information: Zexu Li et al, Association of DNA methylation age acceleration with digital clock drawing test performance: the Framingham Heart Study, Aging-US. DOI: 10.18632/aging.206285

Journal information: Aging-US Provided by Impact Journals LLC