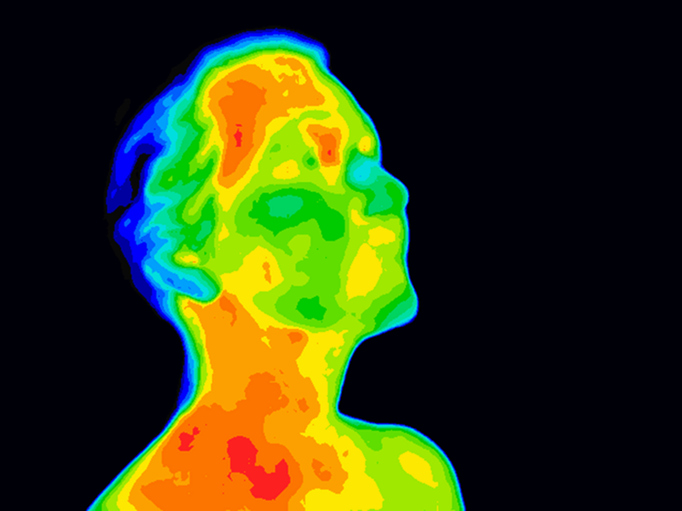

Researchers have identified that variations in facial temperature could indicate high blood pressure, with cooler noses and warmer cheeks serving as potential signs. This discovery arises from findings that link distinct temperatures in various facial regions to chronic diseases like diabetes and hypertension. These subtle thermal differences are invisible to human touch. Still, they can be accurately detected using AI-based analysis of spatial temperature patterns, which requires thermal imaging technology and a data-trained model. This research was detailed in a publication on July 2 in the journal Cell Metabolism, suggesting that with further study, this non-invasive technique could be used by doctors for early disease detection.

Jing-Dong Jackie Han, the study’s corresponding author from Peking University in Beijing, commented on the broader implications of their findings, noting, “Aging is a natural process, but our tool has the potential to promote healthy ageing and help people live disease-free.” The research team had previously utilized 3D facial analysis to predict biological age—an indicator of how well one’s body is ageing and the associated risk of diseases such as cancer and diabetes. Curiosity about whether other facial features like temperature could also indicate health status led to this new avenue of research.

The team analyzed the facial temperatures of over 2,800 Chinese participants ranging from 21 to 88 years old. The data was then used to train AI models that predict a person’s ‘thermal age.’ Key facial regions were identified where temperatures correlated significantly with age and health status, including the nose, eyes, and cheeks. It was found that the temperature of the nose decreases with age more rapidly than other facial areas, suggesting that individuals with warmer noses tend to have a younger thermal age, while temperatures around the eyes generally increase with age.

Furthermore, the study revealed that individuals with metabolic disorders such as diabetes and fatty liver disease experienced faster thermal ageing, often showing higher temperatures in the eye area compared to healthy individuals of the same age. People with elevated blood pressure also exhibited higher temperatures in the cheek areas. The research team attributed these increases in temperature mainly to a rise in cellular activities related to inflammation, including repairing damaged DNA and fighting infections, which heat specific facial regions.

In an exciting twist, the researchers explored whether physical activity could influence thermal age. They instructed 23 participants to jump rope at least 800 times daily for two weeks. To their surprise, participants reduced their thermal age by five years after the exercise regimen, suggesting a profound potential benefit of regular physical activity on one’s thermal and biological ageing.

Looking ahead, Han and her team are keen to investigate whether thermal facial imaging could predict other diseases, such as sleep disorders or cardiovascular issues. “We hope to apply thermal facial imaging in clinical settings, as it holds significant potential for early disease diagnosis and intervention,” Han explains. This advancement in medical imaging, combined with AI technology, offers a promising new frontier in proactively managing health and disease.

More information: Zhengqing Yu et al, Thermal facial image analyses reveal quantitative hallmarks of aging and metabolic diseases, Cell Metabolism. DOI: 10.1016/j.cmet.2024.05.012

Journal information: Cell Metabolism Provided by Cell Press