Alzheimer’s disease (AD) remains one of the most pressing health challenges of our time, affecting more than 55 million people worldwide and accounting for the vast majority of dementia cases. As populations age, the impact of AD grows steadily, placing enormous strain not only on individuals and their families but also on health systems and societies at large. Despite decades of intensive research, there is still no cure, and the treatments currently available provide only modest relief. Unravelling the root causes of the disease is therefore one of the great frontiers in modern medicine, and recent work has begun to cast new light on the role of the immune system in its development.

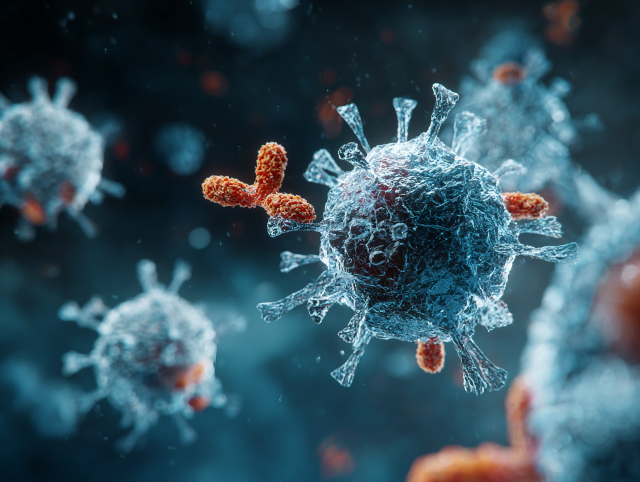

Traditionally, AD has been understood as a disorder driven by the accumulation of two key proteins in the brain: amyloid and tau. Amyloid forms sticky plaques that build up between nerve cells, while tau becomes twisted into tangles inside them. Together, these pathological changes disrupt communication between neurons and progressively erode memory and cognition. In addition, researchers have increasingly recognised that chronic brain inflammation contributes significantly to the disease process. This inflammation was long believed to arise primarily from the brain’s innate immune defences. Still, new findings suggest that the adaptive immune system—the body’s more specialised and long-term defence mechanism—also plays a critical part. This perspective broadens our understanding of AD and opens up new directions for treatment.

To advance this understanding, a team from the Department of Neurology at Fujian Medical University Union Hospital and the Fujian Key Laboratory of Molecular Neurology in China reviewed decades of scientific work examining the involvement of adaptive immunity in AD. Led by Dr Xiaochun Chen, their findings were published in the Chinese Medical Journal on 5 August 2025. Dr Chen emphasised that while the focus of AD research has historically been on amyloid, tau, and innate immunity, their review demonstrates that T cells and B cells—key players in adaptive immunity—are also deeply implicated. This recognition has profound implications, suggesting that Alzheimer’s should be understood as not only a disease of protein misfolding but also one of immune imbalance.

The adaptive immune system is designed to provide targeted, long-lasting defence, mainly through the activity of T and B cells. In AD, evidence suggests that these cells may cross into the brain through a weakened blood–brain barrier, and once inside, they engage in a range of interactions with neural tissue. Specific T cells release inflammatory signals that appear to accelerate damage, while others may counteract harm and offer protection. Similarly, B cells have a dual role: in some instances, they fuel harmful immune responses, but they can also aid in clearing toxic proteins. Dr Chen described this as a “double-edged sword,” where immune cells may simultaneously exacerbate degeneration and provide opportunities for resilience. Understanding how to shift this balance in favour of protective effects is a key challenge for future research.

This shift in perspective has significant therapeutic implications. Recent years have seen considerable debate surrounding immunotherapies targeting amyloid, such as aducanumab and lecanemab, which have yielded mixed outcomes and sparked controversy over their safety and efficacy. The review suggests that broadening the focus to include adaptive immunity could lead to more effective interventions. Potential strategies involve rebalancing the activity of T and B cells, designing vaccines, or tailoring immune-based treatments to individuals with specific genetic risk factors. Such approaches move the field closer to precision medicine, offering the hope of more durable and personalised benefits for patients.

Despite these promising insights, many questions remain. Researchers are still working to clarify how immune cells breach the brain’s protective barriers, why their behaviour varies so markedly among patients, and how age-related changes in the immune system intersect with the biology of AD. These unanswered questions underscore the complexity of the disease but also point to new opportunities for innovation. As Dr Chen observed, adaptive immunity has moved from the margins of Alzheimer’s research to the centre stage. By embracing this broader understanding, scientists may one day harness the immune system not only to slow but perhaps even to prevent AD, providing much-needed hope to patients, families, and the healthcare systems struggling with its growing burden.

More information: Xiaochun Chen et al, Adaptive immunity in the neuroinflammation of Alzheimer’s disease, Chinese Medical Journal. DOI: 10.1097/cm9.0000000000003695

Journal information: Chinese Medical Journal Provided by Chinese Medical Journals Publishing House Co., Ltd.